Creation

1963 photo showing Dr. William H. Pickering, (center) JPL Director, President John F. Kennedy, (right). NASA Administrator James Webb in background. They are discussing the

Mariner program, with a model presented.

On July 29, 1958, Eisenhower signed the

National Aeronautics and Space Act, establishing NASA. When it began operations on October 1, 1958, NASA absorbed the 46-year-old NACA intact; its 8,000 employees, an annual budget of US$100 million, three major research laboratories (

Langley Aeronautical Laboratory,

Ames Aeronautical Laboratory, and

Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory) and two small test facilities.

[14] A

NASA seal was approved by President Eisenhower in 1959.

[15] Elements of the

Army Ballistic Missile Agency and the

United States Naval Research Laboratory were incorporated into NASA. A significant contributor to NASA's entry into the

Space Race with the Soviet Union was the technology from the

German rocket program led by

Wernher von Braun, who was now working for the

Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA), which in turn incorporated the technology of American scientist

Robert Goddard's earlier works.

[16] Earlier research efforts within the

U.S. Air Force[14] and many of ARPA's early space programs were also transferred to NASA.

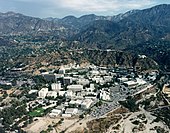

[17] In December 1958, NASA gained control of the

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a contractor facility operated by the

California Institute of Technology.

[14]

Space flight programs

NASA has conducted many manned and unmanned spaceflight programs throughout its history. Unmanned programs launched the first American artificial

satellites into Earth orbit for scientific and

communications purposes, and sent scientific probes to explore the planets of the solar system, starting with

Venus and

Mars, and including "

grand tours" of the outer planets. Manned programs sent the first Americans into

low Earth orbit (LEO), won the

Space Race with the

Soviet Union by landing twelve men on the Moon from 1969 to 1972 in the

Apollo program, developed a semi-reusable LEO

Space Shuttle, and developed LEO

space station capability by itself and with the cooperation of several other nations including post-Soviet

Russia.

Manned programs

The experimental

rocket-powered aircraft programs started by NACA were extended by NASA as support for manned spaceflight. This was followed by a one-man

space capsule program, and in turn by a two-man capsule program. Reacting to loss of national prestige and

securityfears caused by early leads in space exploration by the

Soviet Union, in 1961 President

John F. Kennedy proposed the ambitious goal "of landing a man on the Moon by the end of [the 60s], and returning him safely to the Earth." This goal was met in 1969 by the

Apollo program, and NASA planned even more ambitious activities leading to a

manned mission to Mars. However, reduction of the perceived threat and changing political priorities almost immediately caused the termination of most of these plans. NASA turned its attention to an Apollo-derived temporary space laboratory, and a semi-reusable Earth orbital shuttle. In the 1990s, funding was approved for NASA to develop a permanent Earth orbital

space station in cooperation with the international community, which now included the former rival, post-Soviet

Russia. To date, NASA has launched a total of 166 manned space missions on rockets, and thirteen

X-15 rocket flights above the

USAF definition of spaceflight altitude, 260,000 feet (80 km).

[18]

X-15 rocket plane (1959–68)

The

X-15 was an NACA experimental rocket-powered

hypersonic research aircraft, developed in conjunction with the U.S. Air Force and Navy. The design featured a slender fuselage with fairings along the side containing fuel and early computerized control systems.

[19]Requests for proposal were issued on December 30, 1954 for the airframe, and February 4, 1955 for the rocket engine. The airframe contract was awarded to

North American Aviation in November 1955, and the XLR30 engine contract was awarded to

Reaction Motors in 1956, and three planes were built. The X-15 was

drop-launched from the wing of one of two NASA

Boeing B-52 Stratofortresses,

NB52Atail number 52-003, and

NB52B, tail number 52-008 (known as the

Balls 8). Release took place at an altitude of about 45,000 feet (14 km) and a speed of about 500 miles per hour (805 km/h).

Twelve pilots were selected for the program from the Air Force, Navy, and NACA (later NASA). One hundred ninety-nine flights were made between 1959 and 1968, resulting in the

official world record for the highest speed ever reached by a manned powered aircraft (current as of 2014), and a maximum speed of Mach 6.72, 4,519 miles per hour (7,273 km/h).

[20] The altitude record for X-15 was 354,200 feet (107.96 km).

[21] Eight of the pilots were awarded Air Force

astronaut wings for flying above 260,000 feet (80 km), and two flights by

Joseph A. Walker exceeded 100 kilometers (330,000 ft), qualifying as spaceflight according to the

International Aeronautical Federation. The X-15 program employed mechanical techniques used in the later manned spaceflight programs, including

reaction control system jets for controlling the orientation of a spacecraft, pressurized

space suits, and horizon definition for navigation.

[21] The

reentry and landing data collected were valuable to NASA for designing the

Space Shuttle.

[19]

Project Mercury (1959–63)

Friendship 7, NASA's first manned orbital spaceflight

Mercury-Atlas 6 launch on February 20, 1962

Still frame of John Glenn in orbit from camera inside Friendship 7

Shortly after the

Space Race began, an early objective was to get a person into Earth orbit as soon as possible, therefore the simplest spacecraft that could be launched by existing rockets was favored. U.S. Air Force's

Man in Space Soonest program looked at many manned spacecraft designs, ranging from rocket planes like the X-15, to small ballistic

space capsules.

[22] By 1958, the space plane concepts were eliminated in favor of the ballistic capsule.

[23]

When NASA was created that same year, the Air Force program was transferred to it and renamed

Project Mercury. The

first seven astronauts were selected among candidates from the Navy, Air Force and Marine test pilot programs. On May 5, 1961, astronaut

Alan Shepard became the first American in space aboard

Freedom 7, launched by a

Redstone booster on a 15-minute

ballistic (suborbital) flight.

[24] John Glenn became the first American to be launched into

orbit by an

Atlas launch vehicle on February 20, 1962 aboard

Friendship 7.

[25] Glenn completed three orbits, after which three more orbital flights were made, culminating in

L. Gordon Cooper's 22-orbit flight

Faith 7, May 15–16, 1963.

[26]

Project Gemini (1961–66)

The first rendezvous of two spacecraft, achieved by Gemini 6 and 7

Main article:

Project Gemini

Based on studies to grow the Mercury spacecraft capabilities to long-duration flights, developing

space rendezvous techniques, and precision Earth landing, Project Gemini was started as a two-man program in 1962 to overcome the Soviets' lead and to support the Apollo manned lunar landing program, adding

extravehicular activity (EVA) and

rendezvous and

docking to its objectives. The first manned Gemini flight,

Gemini 3, was flown by

Gus Grissom and

John Young on March 23, 1965.

[28] Nine missions followed in 1965 and 1966, demonstrating an endurance mission of nearly fourteen days, rendezvous, docking, and practical EVA, and gathering medical data on the effects of weightlessness on humans.

[29][30]

Under the direction of Soviet Premier

Nikita Khrushchev, the USSR competed with Gemini by converting their Vostok spacecraft into a two- or three-man

Voskhod. They succeeded in launching two manned flights before Gemini's first flight, achieving a three-cosmonaut flight in 1963 and the first EVA in 1964. After this, the program was then canceled, and Gemini caught up while spacecraft designer

Sergei Korolev developed the

Soyuz spacecraft, their answer to Apollo.

Project Apollo (1961–72)

Main article:

Apollo program

The U.S public's perception of the Soviet lead in putting the first man in space, motivated President

John F. Kennedy to ask the Congress on May 25, 1961 to commit the federal government to a program to land a man on the Moon by the end of the 1960s, which effectively launched the

Apollo program.

[31]

Apollo was one of the most expensive American scientific programs ever. It is estimated to have cost $205 billion in present-day US dollars.

[32][33] (In comparison, the

Manhattan Project cost roughly $26.2 billion, accounting for inflation.)

[32][34] It used the

Saturn rockets as launch vehicles, which were far bigger than the rockets built for previous projects.

[35] The spacecraft was also bigger; it had two main parts, the combined command and service module (CSM) and the lunar landing module (LM). The LM was to be left on the Moon and only the command module (CM) containing the three astronauts would eventually return to Earth.

Buzz Aldrin on the Moon, 1969

The second manned mission,

Apollo 8, brought astronauts for the first time in a flight around the Moon in December 1968.

[36] Shortly before, the Soviets had sent an unmanned spacecraft around the Moon.

[37] On the next two missions docking maneuvers that were needed for the Moon landing were practiced

[38][39] and then finally the Moon landing was made on the

Apollo 11 mission in July 1969.

[40]

The first

person to stand on the Moon was

Neil Armstrong, who was followed by

Buzz Aldrin, while

Michael Collins orbited above. Five subsequent Apollo missions also landed astronauts on the Moon, the last in December 1972. Throughout these six Apollo spaceflights, twelve men walked on the Moon. These missions returned a wealth of scientific data and 381.7 kilograms (842 lb) of lunar samples. Topics covered by experiments performed included

soil mechanics,

meteoroids,

seismology,

heat flow,

lunar ranging,

magnetic fields, and

solar wind.

[41] The Moon landing marked the end of the space race and as a gesture, Armstrong mentioned mankind

[42] when he stepped down on the Moon.

Apollo 17's lunar roving vehicle, 1972

Apollo set major

milestones in human spaceflight. It stands alone in sending manned missions beyond

low Earth orbit, and landing humans on another

celestial body.

[43] Apollo 8 was the first manned spacecraft to orbit another celestial body, while

Apollo 17 marked the last moonwalk and the last manned mission beyond

low Earth orbit. The program spurred advances in many areas of technology peripheral to rocketry and manned spaceflight, including

avionics, telecommunications, and computers. Apollo sparked interest in many fields of engineering and left many physical facilities and machines developed for the program as landmarks. Many objects and artifacts from the program are on display at various locations throughout the world, notably at the

Smithsonian's Air and Space Museums.

Skylab (1965–79)

Skylab space station, 1974

Skylab was the United States' first and only independently built

space station.

[44] Conceived in 1965 as a workshop to be constructed in space from a spent

Saturn IB upper stage, the 169,950 lb (77,088 kg) station was constructed on Earth and launched on May 14, 1973 atop the first two stages of a

Saturn V, into a 235-nautical-mile (435 km) orbit inclined at 50° to the equator. Damaged during launch by the loss of its thermal protection and one electricity-generating solar panel, it was repaired to functionality by its first crew. It was occupied for a total of 171 days by 3 successive crews in 1973 and 1974.

[44] It included a laboratory for studying the effects of

microgravity, and a

solar observatory.

[44] NASA planned to have a Space Shuttle dock with it, and elevate Skylab to a higher safe altitude, but the Shuttle was not ready for flight before Skylab's re-entry on July 11, 1979.

[45]

To save cost, NASA used one of the Saturn V rockets originally earmarked for a canceled Apollo mission to launch the Skylab. Apollo spacecraft were used for transporting astronauts to and from the Skylab. Three three-man crews stayed aboard the station for periods of 28, 59, and 84 days. Skylab's habitable volume was 11,290 cubic feet (320 m

3), which was 30.7 times bigger than that of the

Apollo Command Module.

[45]

Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (1972–75)

Apollo-Soyuz crews with models of spacecraft, 1975

On May 24, 1972, US President

Richard M. Nixon and

Soviet Premier

Alexei Kosygin signed an agreement calling for a joint manned space mission, and declaring intent for all future international manned spacecraft to be capable of docking with each other.

[46] This authorized the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project (ASTP), involving the rendezvous and docking in Earth orbit of a surplus

Apollo Command/Service Module with a

Soyuz spacecraft. The mission took place in July 1975. This was the last US manned space flight until the first orbital flight of the

Space Shuttlein April 1981.

[47]

The mission included both joint and separate scientific experiments, and provided useful engineering experience for future joint US–Russian space flights, such as the Shuttle–Mir Program

[48] and the International Space Station.

Space Shuttle program (1972–2011)

Mission profile. Left: launch, top: orbit (cargo bay open), right: reentry and landing

The

Space Shuttle became the major focus of NASA in the late 1970s and the 1980s. Planned as a frequently launchable and mostly reusable vehicle, four space shuttle orbiters were built by 1985. The first to launch,

Columbia, did so on April 12, 1981,

[49] the 20th anniversary of the first space flight by Yuri Gagarin.

[50]

Its major components were a

spaceplane orbiter with an external fuel tank and two solid fuel launch rockets at its side. The external tank, which was bigger than the spacecraft itself, was the only component that was not reused. The shuttle could orbit in altitudes of 185–643 km (115–400

miles)

[51] and carry a maximum payload (to low orbit) of 24,400 kg (54,000 lb).

[52] Missions could last from 5 to 17 days and crews could be from 2 to 8 astronauts.

[51]

On 20 missions (1983–98) the Space Shuttle carried

Spacelab, designed in cooperation with the

ESA. Spacelab was not designed for independent orbital flight, but remained in the Shuttle's cargo bay as the astronauts entered and left it through an

airlock.

[53] Another famous series of missions were the

launch and later

successful repair of the

Hubble Space Telescope in 1990 and 1993, respectively.

[54]

In 1995 Russian-American interaction resumed with the

Shuttle-Mir missions (1995–1998). Once more an American vehicle docked with a Russian craft, this time a full-fledged space station. This cooperation has continued with Russia and the United States as the two of the biggest partners in the largest space station built: the

International Space Station (ISS). The strength of their cooperation on this project was even more evident when NASA began relying on Russian launch vehicles to service the ISS during the two-year grounding of the shuttle fleet following the 2003

Space Shuttle Columbia disaster.

The Shuttle fleet lost two orbiters and 14 astronauts in two disasters:

Challenger in 1986, and

Columbia in 2003.

[55] While the 1986 loss was mitigated by building the

Space Shuttle Endeavour from replacement parts, NASA did not build another orbiter to replace the

second loss.

[55] NASA's Space Shuttle program had 135 missions when the program ended with the successful landing of the Space Shuttle

Atlantis at the Kennedy Space Center on July 21, 2011. The program spanned 30 years with over 300 astronauts sent into space.

[56]

International Space Station (1993–present)

The International Space Station

The

International Space Station (ISS) combines NASA's

Space Station Freedom project with the Soviet/Russian

Mir-2 station, the European

Columbus station, and the Japanese

Kibō laboratory module.

[57] NASA originally planned in the 1980s to develop

Freedomalone, but US budget constraints led to the merger of these projects into a single multi-national program in 1993, managed by NASA, the

Russian Federal Space Agency (RKA), the

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the

European Space Agency (ESA), and the

Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

[58][59] The station consists of pressurized modules, external

trusses,

solar arrays and other components, which have been launched by Russian

Proton and

Soyuz rockets, and the US Space Shuttles.

[57] It is

currently being assembled in

Low Earth Orbit. The on-orbit assembly began in 1998, the completion of the

US Orbital Segment occurred in 2011 and the completion of the

Russian Orbital Segment is expected by 2016.

[60][61] The ownership and use of the space station is established in intergovernmental treaties and agreements

[62] which divide the station into two areas and allow

Russia to retain full ownership of the Russian Orbital Segment (with the exception of Zarya),

[63][64] with the US Orbital Segment allocated between the other international partners.

[62]

Long duration missions to the ISS are referred to as

ISS Expeditions. Expedition crew members typically spend approximately six months on the ISS.

[65] The initial expedition crew size was three, temporarily decreased to two following the Columbia disaster. Since May 2009, expedition crew size has been six crew members.

[66] Crew size is expected to be increased to seven, the number the ISS was designed for, once the Commercial Crew Program becomes operational.

[67] The ISS has been continuously occupied for the past 13 years and162 days, having exceeded the previous record held by

Mir; and has been visited by astronauts and cosmonauts from

15 different nations.

[68][69]

Spacewalking NASA astronaut in Earth orbit

The station can be seen from the Earth with the naked eye and, as of 2014, is the largest artificial satellite in

Earth orbit with a mass and volume greater than that of any previous space station.

[70]The

Soyuz spacecraft delivers crew members, stays docked for their half-year long missions and then returns them home. Several uncrewed cargo spacecraft service the ISS, they are the Russian

Progress spacecraft which has done so since 2000, the European

Automated Transfer Vehicle(ATV) since 2008, the Japanese

H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV) since 2009, the American

Dragon spacecraft since 2012 and the American

Cygnus spacecraft since 2013. The Space Shuttle, before its retirement, was also used for cargo transfer and would often switch out expedition crew members, although it did not have the capability to remain docked for the duration of their stay. Until another US manned spacecraft is ready, crew members will travel to and from the International Space Station exclusively aboard the Soyuz.

[71] The highest number of people occupying the ISS has been thirteen; this occurred three times during the late Shuttle ISS assembly missions.

[72]

The ISS program is expected to continue until at least 2020 but may be extended until 2028 or possibly beyond that.

[73]

Commercial Resupply Services (2006-present)

The Dragon is seen being berthed to the ISS in May 2012

The Standard variant of Cygnus is seen berthed to the ISS in September 2013

The development of the Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) vehicles began in 2006 with the purpose of creating American commercially operated uncrewed cargo vehicles to service the ISS.

[74] The development of these vehicles was under a fixed price milestone-based program, meaning that each company that received a funded award had a list of milestones with a dollar value attached to them that they didn't receive until after they had successful completed the milestone.

[75] Private companies were also required to have some "skin in the game" which refers raising an unspecified amount of private investment for their proposal.

[76]

Commercial Crew Program (2010–present)

The

Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) program was initiated in 2010 with the purpose of creating American commercially operated crewed spacecraft capable of delivering at least four crew members to the ISS, staying docked for 180 days and then returning them back to Earth.

[82][82] It is hoped that these vehicles could also transport non-NASA customers to private space stations such those planned by

Bigelow Aerospace.

[83] Like COTS, CCDev is also a fixed price milestone-based developmental program that requires some private investment.

[75]

In 2010, NASA announced the winners of the first phase of the program, a total of $50 million was divided among five American companies to foster research and development into human spaceflight concepts and technologies in the private sector. In 2011, the winners of the second phase of the program were announced, $270 million was divided among four companies.

[84] In 2012, the winners of the third phase of the program were announced, NASA provided $1.1 billion divided among three companies to further develop their crew transportation systems.

[85] This phase of the CCDev program is expected to last from June 3, 2012 to May 31, 2014.

[85] The winners of this latest round were SpaceX's

Dragon planned to be launched on a

Falcon 9, Boeing's

CST-100 planned to be launched on an

Atlas V and Sierra Nevada's

Dream Chaser, which is also planned to be launched on an Atlas V.

[86] NASA will most likely only choose one provider for the Commercial Crew program, this vehicle is expected by NASA to become operational around 2017.

[87][88]

The unmanned variant of Dragon is seen approaching the ISS

Computer rendering of CST-100 in orbit

Dream Chaser atmospheric test article

Beyond Low Earth Orbit program (2010–present)

Artist's rendering of the 70 mt variant of SLS launching Orion

For missions beyond

low Earth orbit (BLEO), NASA has been directed to develop the

Space Launch System (SLS), a Saturn-V class rocket, and the two to six person, beyond low Earth orbit spacecraft,

Orion. In February 2010, President

Barack Obama's administration proposed eliminating public funds for the

Constellation program and shifting greater responsibility of servicing the ISS to private companies.

[89] During speech at the Kennedy Space Center on April 15, 2010, Obama proposed the design selection of the new heavy-lift vehicle (HLV) that would replace the formerly planned

Ares V should be delayed until 2015.

[90] He also proposed that the United States should send a crew to an asteroid in the 2020s and send a crew to Mars orbit in the mid-2030s.

[90] The

U.S. Congress drafted the

NASA Authorization Act of 2010 and President Obama signed it into law on October 11 of that year.

[91] The authorization act officially canceled the Constellation program.

[91]

Orion spacecraft design as of January 2013

The Authorization Act required a new HLV design to be chosen within 90 days of its passing and for the construction of a beyond low earth orbit spacecraft.

[92] The authorization act called this new HLV the Space Launch System. The authorization act also required a beyond low Earth orbit spacecraft to be developed, the

Orion spacecraft, which was being developed as part of the Constellation program, was chosen to fulfill this role.

[93] The Space Launch System is planned to launch both Orion and other necessary hardware for missions beyond low Earth orbit.

[94] The SLS is to be upgraded over time with more powerful versions. The initial capability of SLS is required to be able to lift 70 mt into

LEO, it is then planned to be upgraded to 105 mt and then eventually to 130 mt.

[93][95]

Exploration Flight Test 1 (EFT-1), an unmanned test flight of Orion's crew module, is planned to be launched in 2014 on a

Delta IV Heavyrocket.

[95] Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1) is the unmanned initial launch of SLS that would also send Orion on a

circumlunar trajectory, which is planned for 2017.

[95] The first manned flight of Orion and SLS, Exploration Mission 2 (EM-2) is to launch between 2019 and 2021; it is a 10- to 14-day mission planned to place a crew of four into

Lunar orbit.

[95] As of March 2012, the destination for EM-3 and the intermediate focus for this new program is still in-flux.

[96]

Unmanned programs

Deep space mission deployed by Shuttle, 1989

More than 1,000 unmanned missions have been designed to explore the Earth and the solar system.

[97] Besides exploration, communication satellites have also been launched by NASA.

[98] The missions have been launched directly from Earth or from orbiting space shuttles, which could either deploy the satellite itself, or with a rocket stage to take it farther.

The first US unmanned satellite was

Explorer 1, which started as an ABMA/JPL project during the early space race. It was launched in January 1958, two months after Sputnik. At the creation of NASA the Explorer project was transferred to this agency and still continues to this day. Its missions have been focusing on the Earth and the Sun, measuring magnetic fields and the

solar wind, among other aspects.

[99] A more recent Earth mission, not related to the Explorer program, was the

Hubble Space Telescope, which as mentioned above was brought into orbit in 1990.

[100]

The

inner Solar System has been made the goal of at least four unmanned programs. The first was

Mariner in the 1960s and 70s, which made multiple visits to

Venus and

Mars and one to

Mercury. Probes launched under the Mariner program were also the first to make a planetary flyby (

Mariner 2), to take the first pictures from another planet (

Mariner 4), the first planetary orbiter (

Mariner 9), and the first to make a

gravity assistmaneuver (

Mariner 10). This is a technique where the satellite takes advantage of the gravity and velocity of planets to reach its destination.

[101]

Outside Mars, Jupiter was first visited by

Pioneer 10 in 1973. More than 20 years later

Galileo sent a probe into the planet's atmosphere, and became the first spacecraft to orbit the planet.

[103] Pioneer 11 became the first spacecraft to visit

Saturn in 1979, with

Voyager 2making the first (and so far only) visits to

Uranus and

Neptune in 1986 and 1989, respectively. The first spacecraft to leave the solar system was Pioneer 10 in 1983.

[104] For a time it was the most distant spacecraft, but it has since been surpassed by both

Voyager 1 and

Voyager 2.

[105]

Pioneers 10 and 11 and both Voyager probes carry messages from the Earth to extraterrestrial life.

[106][107] A problem with deep space travel is communication. For instance, it takes about 3 hours at present for a radio signal to reach the New Horizons spacecraft at a point more than halfway to Pluto.

[108] Contact with Pioneer 10 was lost in 2003. Both Voyager probes continue to operate as they explore the outer boundary between the Solar System and interstellar space.

[109]

Artist's concept of NASA's Intelligent Payload Experiment (IPEX) and M-Cubed/COVE-2 satellites ("CubeSats") that were launched as part of the NROL-39 GEMSat mission in December 2013.

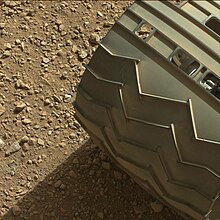

On November 26, 2011, NASA's

Mars Science Laboratory mission was successfully launched for Mars.

Curiosity successfully landed on Mars on August 6, 2012, and subsequently began its search for evidence of past or present life on Mars.

[110][111][112]

Recent and planned activities

NASA's ongoing investigations include in-depth surveys of Mars and Saturn and studies of the Earth and the Sun. Other active spacecraft missions are

MESSENGER for

Mercury, New Horizons (for Jupiter,

Pluto, and beyond), and

Dawn for the

asteroid belt. NASA continued to support

in situ exploration beyond the asteroid belt, including Pioneer and Voyager traverses into the unexplored trans-Pluto region, and

Gas Giant orbiters Galileo (1989–2003), Cassini (1997–), and Juno (2011–).

Vision mission for an interstellar precursor spacecraft by NASA

On December 4, 2006, NASA announced it was planning a

permanent moon base.

[114] The goal was to start building the moon base by 2020, and by 2024, have a fully functional base that would allow for crew rotations and

in-situ resource utilization. However in 2009, the

Augustine Committee found the program to be on a "unsustainable trajectory."

[115] In 2010, President

Barack Obama halted existing plans, including the Moon base, and directed a generic focus on manned missions to asteroids and Mars, as well as extending support for the International Space Station.

[116]

Since 2011, NASA's strategic goals have been

[117]

- Extend and sustain human activities across the solar system

- Expand scientific understanding of the Earth and the universe

- Create innovative new space technologies

- Advance aeronautics research

- Enable program and institutional capabilities to conduct NASA's aeronautics and space activities

- Share NASA with the public, educators, and students to provide opportunities to participate

On August 6, 2012, NASA landed the rover

Curiosity on Mars. On August 27, 2012,

Curiosity transmitted the first pre-recorded message from the surface of Mars back to Earth, made by Administrator Charlie Bolden:

Hello. This is Charlie Bolden, NASA Administrator, speaking to you via the broadcast capabilities of the Curiosity Rover, which is now on the surface of Mars.

Since the beginning of time, humankind’s curiosity has led us to constantly seek new life…new possibilities just beyond the horizon. I want to congratulate the men and women of our NASA family as well as our commercial and government partners around the world, for taking us a step beyond to Mars.

This is an extraordinary achievement. Landing a rover on Mars is not easy – others have tried – only America has fully succeeded. The investment we are making…the knowledge we hope to gain from our observation and analysis of Gale Crater, will tell us much about the possibility of life on Mars as well as the past and future possibilities for our own planet. Curiosity will bring benefits to Earth and inspire a new generation of scientists and explorers, as it prepares the way for a human mission in the not too distant future. Thank you.

[121]

Scientific research

Mars rock, viewed by a rover

Medicine in space

Main article:

Space medicine

A variety of large-scale medical studies are being conducted in space by the

National Space Biomedical Research Institute (NSBRI). Prominent among these is the

Advanced Diagnostic Ultrasound in Microgravity Study, in which astronauts (including former ISS Commanders

Leroy Chiao and

Gennady Padalka) perform ultrasound scans under the guidance of remote experts to diagnose and potentially treat hundreds of medical conditions in space. Usually there is no physician on board the International Space Station, and

diagnosis of medical conditions is challenging. Astronauts are susceptible to a variety of health risks including

decompression sickness, barotrauma, immunodeficiencies, loss of bone and muscle, orthostatic intolerance due to volume loss,

sleep disturbances, and radiation injury.

Ultrasound offers a unique opportunity to monitor these conditions in space. This study's techniques are now being applied to cover professional and Olympic sports injuries as well as ultrasound performed by non-expert operators in populations such as medical and high school students. It is anticipated that remote guided ultrasound will have application on Earth in emergency and rural care situations, where access to a trained physician is often rare.

[122][123][124]

Ozone depletion

Salt evaporation and energy management

In one of the nation's largest restoration projects, NASA technology helps state and federal government reclaim 15,100 acres (61 km

2) of salt evaporation ponds in South San Francisco Bay. Satellite sensors are used by scientists to study the effect of salt evaporation on local ecology.

[127]

NASA has started Energy Efficiency and Water Conservation Program as an agency-wide program directed to prevent pollution and reduce energy and water utilization. It helps to ensure that NASA meets its federal stewardship responsibilities for the environment.

[128]

Earth science

Plot of orbits of known Potentially Hazardous Asteroids (size over 460 feet (140 m) and passing within 4.7 million miles (7.6

×106 km) of Earth's orbit) circa 2013 (

alternate image).

Understanding of natural and human-induced changes on the global environment is the main objective of NASA's

Earth science. NASA currently has more than a dozen Earth science spacecraft/instruments in orbit studying all aspects of the Earth system (oceans, land, atmosphere,

biosphere,

cryosphere), with several more planned for launch in the next few years.

[129]

NASA is working in cooperation with

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). The goal is to produce worldwide solar resource maps with great local detail.

[130] NASA was also one of the main participants in the evaluation innovative technologies for the cleanup of the sources for

dense non-aqueous phase liquids (DNAPLs). On April 6, 1999, the agency signed The

Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) along with the

United States Environmental Protection Agency,

DOE, and

USAF authorizing all the above organizations to conduct necessary tests at the John F. Kennedy Space center. The main purpose was to evaluate two innovative in-situ remediation technologies, thermal removal and oxidation destruction of DNAPLs.

[131] National Space Agency made a partnership with Military Services and

Defense Contract Management Agency named the “Joint Group on Pollution Prevention”. The group is working on reduction or elimination of hazardous materials or processes.

[132]

Staff and leadership

NASA's administrator is the agency's highest-ranking official and serves as the senior space science adviser to the President of the United States. The agency's administration is located at

NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC and provides overall guidance and direction.

[134] Except under exceptional circumstances, NASA civil service employees are required to be

citizens of the United States.

[135]

The third administrator was

James E. Webb (served 1961–1968), appointed by President

John F. Kennedy. In order to implement the

Apollo program to achieve Kennedy's goal of landing a man on the Moon by 1970, Webb directed major management restructuring and facility expansion, establishing the Houston Manned Spacecraft (Johnson) Center and the Florida Launch Operations (Kennedy) Center.

Facilities

John F. Kennedy Space Center (KSC), is one of the best-known NASA facilities. It has been the launch site for every United States human space flight since 1968. Although such flights are currently on pause, KSC continues to manage and operate unmanned rocket launch facilities for America's civilian space program from three pads at the adjoining Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.

Another major facility is

Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama at which the Saturn 5 rocket and Skylab were developed.

[138] The

JPL, mentioned above, was together with

ABMA one of the agencies behind

Explorer 1, the first American space mission.

Budget

NASA's budget 1962–2014 as % of federal budget peaking 1966

Main article:

Budget of NASA

NASA's budget has generally been approximately 1% of the federal budget from the early 1970s on, but briefly peaked to approximately 4.41% in 1966 during the Apollo program.

[139] Recent public perception of the NASA budget has been shown to be significantly different from reality; a 1997 poll indicated that Americans responded on average that 20% of the federal budget went to NASA.

[140]

The percentage of federal budget that NASA has been allocated has been steadily dropping since the Apollo program and as of 2012 the NASA budget is estimated to be 0.48% of the federal budget.

[141] In a March 2012 meeting of the

United States Senate Science Committee,

Neil deGrasse Tyson testified that "Right now, NASA’s annual budget is half a penny on your tax dollar. For twice that—a penny on a dollar—we can transform the country from a sullen, dispirited nation, weary of economic struggle, to one where it has reclaimed its 20th century birthright to dream of tomorrow."

[142][143] Inspired by Tyson's advocacy and remarks, the

Penny4NASAnonprofit was founded in 2012 to advocate the doubling of NASA's budget to one percent of the Federal Budget, or one "penny on the dollar."

[144]

Current missions

Various nebulae observed from a NASA space telescope

Examples of some current NASA missions:

See also

References

- Jump up^ Lale Tayla and Figen Bingul (2007). "NASA stands "for the benefit of all."—Interview with NASA's Dr. Süleyman Gokoglu". The Light Millennium.

- Jump up^ U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission, NACA. centennialofflight.net. Retrieved on 2011-11-03.

- Jump up^ "NASA workforce profile". NASA. January 11, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- Jump up^ Teitel, Amy (December 2, 2011). "A Mixed Bag for NASA's 2012 Budget". DiscoveryNews. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- Jump up^ "Ike in History: Eisenhower Creates NASA". Eisenhower Memorial. 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- Jump up^ "The National Aeronautics and Space Act". NASA. 2005. Retrieved August 29, 2007.

- Jump up^ Bilstein, Roger E. (1996). "From NACA to NASA". NASA SP-4206, Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicles. NASA. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-16-004259-1. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- Jump up^ Netting, Ruth (June 30, 2009). "Earth—NASA Science". Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Jump up^ Netting, Ruth (January 8, 2009). "Heliophysics—NASA Science". Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Jump up^ Netting, Ruth (January 8, 2009). "Planets—NASA Science". Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Jump up^ Netting, Ruth (July 13, 2009). "Astrophysics—NASA Science". Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Jump up^ "The NACA, NASA, and the Supersonic-Hypersonic Frontier". NASA. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Jump up^ Subcommittee On Military Construction, United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Armed Services (January 21, 24, 1958). Supplemental military construction authorization (Air Force).: Hearings, Eighty-fifth Congress, second session, on H.R. 9739..

- ^ Jump up to:a b c "T. KEITH GLENNAN". NASA. August 4, 2006. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Jump up^ Executive Order 10849 (Wikisource)

- Jump up^ von Braun, Werner (1963). "Recollections of Childhood: Early Experiences in Rocketry as Told by Werner Von Braun 1963". MSFC History Office. NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Jump up^ Van Atta, Richard (April 10, 2008). 50 years of Bridging the Gap (PDF). Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Jump up^ The Air Force definition of outer space differs from that of the International Aeronautical Federation, which is 100 kilometers (330,000 ft).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Aerospaceweb, North American X-15. Aerospaceweb.org. Retrieved on 2011-11-03.

- Jump up^ Aircraft Museum X-15." Aerospaceweb.org, 24 November 2008.

- ^ Jump up to:a b NASA, X-15 Hypersonic Research Program, retrieved 2011-10-17

- Jump up^ Encyclopedia Astronautica, Project 7969, retrieved 2011-10-17

- Jump up^ NASA, Project Mercury Overview, retrieved 2011-10-17

- Jump up^ Swenson Jr., Loyd S.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. (1989). 11-4 Shepard's Ride. In Woods, David; Gamble, Chris. "This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury" (url). Published as NASA Special Publication-4201 in the NASA History Series (NASA). Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Jump up^ Swenson Jr., Loyd S.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. (1989). 13-4 An American in Orbit. In Woods, David; Gamble, Chris. "This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury" (url). Published as NASA Special Publication-4201 in the NASA History Series (NASA). Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Jump up^ "Mercury Manned Flights Summary". NASA. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- Jump up^ "NASA history, Gagarin". NASA. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- Jump up^ Barton C. Hacker; James M. Grimwood (December 31, 2002). "10-1 The Last Hurdle". On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini (url). NASA.ISBN 978-0-16-067157-9. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Jump up^ Barton C. Hacker; James M. Grimwood (December 31, 2002). "12-5 Two Weeks in a Spacecraft". On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini. NASA.ISBN 978-0-16-067157-9. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Jump up^ Barton C. Hacker; James M. Grimwood (December 31, 2002). "13-3 An Alternative Target". On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini. NASA. ISBN 978-0-16-067157-9. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Jump up^ John F. Kennedy "Landing a man on the Moon" Address to Congress on YouTube, speech

- ^ Jump up to:a b Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2014. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- Jump up^ Butts, Glenn; Linton, Kent (April 28, 2009). "The Joint Confidence Level Paradox: A History of Denial, 2009 NASA Cost Symposium". pp. 25–26.

- Jump up^ Nichols, Kenneth David (1987). The Road to Trinity: A Personal Account of How America's Nuclear Policies Were Made, pp 34–35. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-06910-X. OCLC 15223648.

- Jump up^ "Saturn V". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- Jump up^ "Apollo 8: The First Lunar Voyage". NASA. Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- Jump up^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2003). The Soviet Space Race with Apollo. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. pp. 654–656. ISBN 0-8130-2628-8.

- Jump up^ "Apollo 9: Earth Orbital trials". NASA. Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- Jump up^ "Apollo 10: The Dress Rehearsal". NASA. Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- Jump up^ "The First Landing". NASA. Retrieved 2011-10-13.

- Jump up^ Chaikin, Andrew (March 16, 1998). A Man on the Moon. New York: Penguin Books.ISBN 978-0-14-027201-7.

- Jump up^ The Phrase Finder:...a giant leap for mankind, retrieved 2011-10-01

- Jump up^ 30th Anniversary of Apollo 11, Manned Apollo Missions. NASA, 1999.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Belew, Leland F., ed. (1977). Skylab Our First Space Station—NASA report(PDF). NASA. NASA-SP-400. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Benson, Charles Dunlap and William David Compton. Living and Working in Space: A History of Skylab. NASA publication SP-4208.

- Jump up^ Gatland, Kenneth (1976). Manned Spacecraft, Second Revision. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. p. 247. ISBN 0-02-542820-9.

- Jump up^ Grinter, Kay (April 23, 2003). "The Apollo Soyuz Test Project". Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Jump up^ NASA, Shuttle-MIR history, retrieved 2011-10-15

- Jump up^ Bernier, Serge (May 27, 2002). Space Odyssey: The First Forty Years of Space Exploration. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81356-3.

- Jump up^ Encyclopedia Astronautica, Vostok 1, retrieved 2011-10-18

- ^ Jump up to:a b NASA, Shuttle Basics, retrieved 2011-10-18

- Jump up^ Encyclopedia Astronautica, Shuttle, retrieved 2011-10-18

- Jump up^ Encyclopedia Astronautica, Spacelab. Retrieved October 20, 2011

- Jump up^ Encyclopedia Astronautica, HST. Retrieved October 20, 2011

- ^ Jump up to:a b Watson, Traci (January 8, 2008). "Shuttle delays endanger space station". USA Today. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Jump up^ "NASA's Last Space Shuttle Flight Lifts Off From Cape Canaveral". KHITS Chicago. July 8, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b John E. Catchpole (17 June 2008). The International Space Station: Building for the Future. Springer-Praxis. ISBN 978-0-387-78144-0.

- Jump up^ "Human Spaceflight and Exploration—European Participating States". European Space Agency (ESA). 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- Jump up^ Gary Kitmacher (2006). Reference Guide to the International Space Station. Canada:Apogee Books. pp. 71–80. ISBN 978-1-894959-34-6. ISSN 1496-6921.

- Jump up^ Gerstenmaier, William (2011-10-12). "Statement of William H. Gerstenmaier Associate Administrator for HEO NASA before the Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics Committee on Science, Space and Technology U. S. House of Representatives". United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- Jump up^ Afanasev, Igor; Vorontsov, Dmitrii (11 January 2012). "The Russian ISS segment is to be completed by 2016". Air Transport Observer. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "ISS Intergovernmental Agreement". European Space Agency (ESA). 19 April 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- Jump up^ "Memorandum of Understanding Between the National Aeronautics and Space Administration of the United States of America and the Russian Space Agency Concerning Cooperation on the Civil International Space Station". NASA. 29 January 1998. Retrieved 19 April 2009.

- Jump up^ Zak, Anatoly (15 October 2008). "Russian Segment: Enterprise". RussianSpaceWeb. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- Jump up^ "ISS Fact sheet: FS-2011-06-009-JSC". NASA. 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Jump up^ "MCB Joint Statement Representing Common Views on the Future of the ISS". International Space Station Multilateral Coordination Board. 3 February 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- Jump up^ Leone, Dan (20 June 2012). "Wed, 20 June, 2012 NASA Banking on Commercial Crew To Grow ISS Population". Space News. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Jump up^ "Nations Around the World Mark 10th Anniversary of International Space Station". NASA. 17 November 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- Jump up^ Boyle, Rebecca (11 November 2010). "The International Space Station Has Been Continuously Inhabited for Ten Years Today". Popular Science. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- Jump up^ International Space Station, Retrieved October 20, 2011

- Jump up^ Chow, Denise (17 November 2011). "U.S. Human Spaceflight Program Still Strong, NASA Chief Says". Space.com. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- Jump up^ Potter, Ned (17 July 2009). "Space Shuttle, Station Dock: 13 Astronauts Together". ABC News. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- Jump up^ Leone, Dan (29 March 2012). "Sen. Mikulski Questions NASA Commercial Crew Priority". Space News. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- Jump up^ "NASA Selects Crew and Cargo Transportation to Orbit Partners" (Press release). NASA. 2006-08-18. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Moving Forward: Commercial Crew Development Building the Next Era in Spaceflight". Rendezvous. NASA. 2010. pp. 10–17. Retrieved February 14, 2011. "Just as in the COTS projects, in the CCDev project we have fixed-price, pay-for-performance milestones," Thorn said. "There’s no extra money invested by NASA if the projects cost more than projected."

- Jump up^ McAlister, Phil (October 2010). "The Case for Commercial Crew". NASA. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- Jump up^ "NASA Awards Space Station Commercial Resupply Services Contracts". NASA, December 23, 2008.

- Jump up^ "Space Exploration Technologies Corporation – Press". Spacex.com. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- Jump up^ Clark, Stephen (2 June 2012). "NASA expects quick start to SpaceX cargo contract". SpaceFlightNow. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- Jump up^ Bergin, Chris (28 September 2013). "Orbital’s Cygnus successfully berthed on the ISS". NASASpaceFlight.com (not affiliated with NASA). Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- Jump up^ "SpaceX/NASA Discuss launch of Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon capsule". NASA. 22 May 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Berger, Brian (2011-02-01). "Biggest CCDev Award Goes to Sierra Nevada". Imaginova Corp. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- Jump up^ Morring, Frank (10 October 2012). "Boeing Gets Most Money With Smallest Investment". Aviation Week. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- Jump up^ Dean, James. "NASA awards $270 million for commercial crew efforts" at theWayback Machine (archived May 11, 2011). space.com, April 18, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "NASA Announces Next Steps in Effort to Launch Americans from U.S. Soil". NASA. August 3, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- Jump up^ Five Vehicles Vie For Future Of U.S. Human Spaceflight

- Jump up^ "Recent Developments in NASA’s Commercial Crew Acquisition Strategy". United States House Committee on Science, Space and Technology. 14 September 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- Jump up^ "Congress wary of fully funding commercial crew". Spaceflightnow. 2012-04-24. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Jump up^ Achenbach, Joel (February 1, 2010). "NASA budget for 2011 eliminates funds for manned lunar missions". Washington Post. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "President Barack Obama on Space Exploration in the 21st Century". Office of the Press Secretary. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Today – President Signs NASA 2010 Authorization Act". Universetoday.com. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- Jump up^ Svitak, Amy (31 March 2011). "Holdren: NASA Law Doesn’t Square with Budgetary Reality". Space News. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b S.3729 – National Aeronautics and Space Administration Authorization Act of 2010

- Jump up^ "NASA Announces Design for New Deep Space Exploration System". NASA. 2011-09-14. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Bergin, Chris (2012-02-23). "Acronyms to Ascent – SLS managers create development milestone roadmap". NASA. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- Jump up^ Bergin, Chris (2012-03-26). "NASA Advisory Council: Select a Human Exploration Destination ASAP". NasaSpaceflight (not affiliated with NASA). Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Jump up^ "Launch History (Cumulative)". NASA. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Jump up^ "NASA Experimental Communications Satellites, 1958–1995". NASA. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Jump up^ "NASA, Explorers program". NASA. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- Jump up^ NASA mission STS-31 (35) Archived 18 August 2011 at WebCite

- Jump up^ "JPL, Chapter 4. Interplanetary Trajectories". NASA. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Jump up^ "Missions to Mars". The Planet Society. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Jump up^ "Missions to Jupiter". The Planet Society. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Jump up^ "What was the first spacecraft to leave the solar system". Wikianswers. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Jump up^ "JPL Voyager". JPL. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Jump up^ "Pioneer 10 spacecraft send last signal". NASA. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Jump up^ "The golden record". JPL. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Jump up^ "New Horizon". JHU/APL. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Jump up^ "Voyages Beyond the Solar System: The Voyager Interstellar Mission". NASA. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- Jump up^ NASA Staff (November 26, 2011). "Mars Science Laboratory". NASA. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- Jump up^ "NASA Launches Super-Size Rover to Mars: 'Go, Go!'". New York Times. Associated Press. November 26, 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-26.

- Jump up^ Kenneth Chang (August 6, 2012). "Curiosity Rover Lands Safely on Mars". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-08-06.

- Jump up^ Wilson, Jim (September 15, 2008). "NASA Selects 'MAVEN' Mission to Study Mars Atmosphere". NASA. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Jump up^ NASA Office of Public Affairs (December 4, 2006). "GLOBAL EXPLORATION STRATEGY AND LUNAR ARCHITECTURE" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Jump up^ "Review of United States Human Space Flight Plans Committee". Office of Science and Technology Policy. October 22, 2009. Retrieved December 13, 2011.

- Jump up^ Goddard, Jacqui (February 2, 2010). "Nasa reduced to pipe dreams as Obama cancels Moon flights". The Times (London). Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- Jump up^ "NASA Strategic Plan, 2011". NASA Headquarters.

- Jump up^ Boyle, Rebecca (June 5, 2012). "NASA Adopts Two Spare Spy Telescopes, Each Maybe More Powerful than Hubble". Popular Science. Popular Science Technology Group. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- Jump up^ "NASA Announces Design for New Deep Space Exploration System". NASA. September 14, 2011. Retrieved December 13, 2011.

- Jump up^ Bergin, Chris (November 6, 2011). "NASA managers approve EFT-1 flight as Orion pushes for orbital debut". NASASpaceFlight.com (Not affiliated with NASA). Retrieved December 13, 2011.

- Jump up^ 08.27.2012 First Recorded Voice from Mars

- Jump up^ "NASA—Advanced Diagnostic Ultrasound in Microgravity (ADUM)". NASA. July 31, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- Jump up^ Rao, S; Van Holsbeeck, L; Musial, JL; Parker, A; Bouffard, JA; Bridge, P; Jackson, M; Dulchavsky, SA (2008). "A pilot study of comprehensive ultrasound education at the Wayne State University School of Medicine: a pioneer year review". Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine 27 (5): 745–9. PMID 18424650.

- Jump up^ Fincke, E. M.; Padalka, G.; Lee, D.; Van Holsbeeck, M.; Sargsyan, A. E.; Hamilton, D. R.; Martin, D.; Melton, S. L.; McFarlin, K.; Dulchavsky, S. A. (2005). "Evaluation of Shoulder Integrity in Space: First Report of Musculoskeletal US on the International Space Station". Radiology 234 (2): 319–22. doi:10.1148/radiol.2342041680.PMID 15533948.

- Jump up^ W. Henry Lambright (May 2005). "NASA and the Environment: The Case of Ozone Depletion". NASA. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- Jump up^ Dr. Richard McPeters (2008). "Ozone Hole Monitoring". NASA. Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- Jump up^ "NASA Helps Reclaim 15,100 Acres Of San Francisco Bay Salt Ponds". Space Daily. 2003. Archived from the original on May 23, 2011. Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- Jump up^ Tina Norwood (2007). "Energy Efficiency and Water Conservation". NASA. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- Jump up^ "Taking a global perspective on Earth's climate". Global Climate Change: NASA's Eyes on the Earth. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011.

- Jump up^ D. Renné, S. Wilcox, B. Marion, R. George, D. Myers, T. Stoffel, R. Perez, P. Stackhouse, Jr. (2003). "Progress on Updating the 1961–1990 National Solar Radiation Database". NREL. Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- Jump up^ EPA (1999). "EPA, DOE, NASA AND USAF Evaluate Innovative Technologies". EPA. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- Jump up^ Benjamin S. Griffin, Gregory S. Martin, Keith W. Lippert, J.D.MacCarthy, Eugene G. Payne, Jr. (2007). "Joint Group on Pollution Prevention". NASA. Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- Jump up^ Michael K. Ewert (2006). "Johnson Space Center's Role in a Sustainable Future". NASA. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- Jump up^ Shouse, Mary (July 9, 2009). "Welcome to NASA Headquarters". Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Jump up^ Information for Non U.S. Citizens, NASA (downloaded 16 September 2013)

- Jump up^ "T. Keith Glennan biography". NASA. August 4, 2006. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- Jump up^ Cabbage, Michael (July 15, 2009). "Bolden and Garver Confirmed by U.S. Senate"(Press release). NASA. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- Jump up^ "MSFC_Fact_sheet". NASA. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- Jump up^ Rogers, Simon. (2010-02-01) Nasa budgets: US spending on space travel since 1958 | Society. theguardian.com. Retrieved on 2013-08-26.

- Jump up^ Launius, Roger D. "Public opinion polls and perceptions of US human spaceflight". Division of Space History, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

- Jump up^ "Fiscal Year 2013 Budget Estimates". NASA. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- Jump up^ "Past, Present, and Future of NASA - U.S. Senate Testimony". Hayden Planetarium. 7 Mar 2012. Retrieved 4 Dec 2012.

- Jump up^ "Past, Present, and Future of NASA - U.S. Senate Testimony (Video)". Hayden Planetarium. 7 Mar 2012. Retrieved 4 Dec 2012.

- Jump up^ "Why We Fight - Penny4NASA". Penny4NASA. Retrieved 30 Nov 2012.

External links

This audio file was created from a revision of the "

NASA" article dated September 1, 2005, and does not reflect subsequent edits to the article. (

Audio help)

- General

- Further reading